Editing makes all disciplines in film come together, and could easily be considered the foundation of a film’s pace, atmosphere and story. This makes editing quite a topic of interest, however, most good editing goes by unnoticed which makes the subject a challenge to study. In this article we hand you 20 ‘invisible’ techniques to get the most out of your edit and to make your edit unseen.

“Editing is control and manipulation. We are controlling reality as the audience sees it and therefore controlling the audience’s response. Whether it’s a laugh or a sigh or a fright, in a way, it has all been manipulated. ” – Michael Kahn

The stylistic manner of a cut can add depth to a films tone because of the psychological suggestions it offers to the way we watch. We can cut from one scene to another with an establishing shot, however, this doesn’t emotionally affect us.

1. Cutting on Action

Cutting on the action is often used as a way to make an activity look more vital by cutting from one shot to another shot with a different view on the first shot, placing the cut there where it matches the first shot’s action. The goal of such an ‘action-cut’ is to preserve the continuity and flow of your edit, making the switch in angle more invisible and the sequence more dynamic; allowing the action to determine the cut and not the other way round.

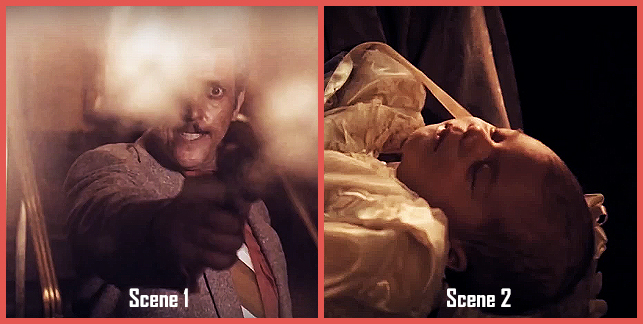

2. Merging two Worlds

However, a less conventional but very powerful purpose of cutting on action is to not aesthetically enhance a certain action, but to suggest a consuming solitary goal on the characters mind; the subjects thoughts are transfixed elsewhere. By cutting on the action in one situation to an action in a different time or place, one life invades the other like a random neural connection.

Tip: A purposeful application of cutting on action demands planning. Use a storyboard to plan the connecting shots to create a seamless edit.

3. Holding it Long

Sometimes not placing a cut, but holding it long instead actually tells the viewer more. Your audience is being dragged out of their comfortable observation mode and is suddenly provoked by an element of unease. A seemingly empty shot can become powerful and full of content once given a lengthy appearance. Such shots arouse suspicion and promise a resolve of some kind, especially when combined with the Kubrick Zoom( see technique 9). Editing is not only about where we cut, but also about where we didn’t cut.

Tip: Emotion needs time to transmit from the screen to the heart, and not every viewer connects as easily with your characters as you as a film-maker do (given that you are far more familiar with a characters backstory and motives). Keep this in mind when trying to convey emotions in your audience; try to hold the shot a little, little longer than you are comfortable viewing to make sure your audience can ‘feel’ the shot as you on the maker’s side can.

4. The Gilligan Cut

A Gilligan Cut or Smash Cut is used when you’re transitioning between two completely different scenes, emotions, or narratives and when you need to make an abrupt transition to startle, and gain an instantaneous response or to show the distinction between two polarizing worlds. A smash cut can be applied in both audio and visual means. If you have got a loud scene that immediately goes to a quiet scene or vice versa, this is where you’d use the smash cut in sound.

Tip: The Gilligan Cut has proven its use very well in comedic relief. A very popular example would be to have a character swear a particular something would never, ever happen to him to then cut to the next shot of him in that exact situation. Simplicity at its simplest.

5. The J-cut / L-cut

The J-cut and L-cut already tell you what they stand for by simply looking at their shapes. In a J-cut sound the audio of the next scene precedes the picture while an L-cut means that the picture changes but the audio continues (think of your video and audio track on top of each other for the visual cue). This technique is often used to make a cut feel less harsh.

6. Eyeline Matching

Another way of making your editing more invisible is through eyeline matching. The basic premise of eyeline matching is that the viewers will want to see what the character they are watching on the screen is viewing. If a character is looking at something off-screen, the next shot should tell us what our character is looking at. This works best when the reverse shot is filmed from the characters POV. The eyeline match creates order and meaning in cinematic space.

Tip: When shooting eyeline matching shots on set, it can be an immense help to give the actor a mark to look at off-camera to help establish a correct eye-line. To get the most out of your eyeline shot, if often works best to have a MS look at a MS, and a CU to a CU. Also consider the height of your actors as well as the height of the object/actor they are looking at to get the POV angle right.

7. Establishing shots.

8. The ‘Kubrick’ Zoom

Often times a zoom (either in post or during production) is used as a way to drag the viewer not just visually but mentally closer to the meaning of the shot. Its a great tool to heighten the suspense or action of a scene. Stanley Kubrick is famous for his clever application of the zooming feature, using the tool in a slightly different sense; instead of your typical exclamation mark zoom more as a ‘dot-dot-dot’.

The Kubrick Zoom is often unaccompanied by dialogue, instead it’s just the object and the camera interacting; the former passively and the latter actively. The zooming out is often used to introduce new elements in the frame, and the zooming in to create an almost claustrophobic sense of linger. This carefully composed, slow movement establishes an unbelievable feeling of unease and fear and shares an unusual intimacy with the audience.

9. Parallel Editing

Parallel editing ( or cross cutting ) is the technique of continuously alternating two or more scenes that ( often but not necessarily ) happen simultaneously, but in different locations. This way you can show a correlation, or contrast between two events or characters, allowing complex and subtle relationships to establish themselves by way of cinematic proximity.